Songlines Review Spring/Summer 2001

Tony MacMahon

Mac Mahon From Clare

Maccd 001 (69mins)

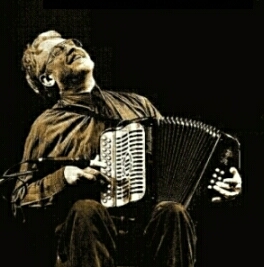

Even if he wasn’t the man who first brought The Bothy Band together to perform on his RTÉ radio programme The Long Note, accordionist Tony Mac Mahon’s place in Ireland’s traditional music pantheon would nonetheless be secure.

Mentored during his early years by the late greats Joe Cooley and Seamus Ennis, he is especially esteemed for his interpretation of slow airs, often described as possessing the lonesome quality or draiocht associated with Irish traditional music at its best. Mac Mahon has collected five superlative examples on this – his first solo release since 1972 – gleaned from archival recordings made between 1967 and 2000. Among them are several sparkling duos with various ‘brothers in music,’ including fiddlers James Kelly and Seamus Connolly, Barney McKenna on banjo, the late Peadar Mercier, bodhran player with The Chieftains, plus a brief but memorable appearance of the aforementioned Cooley, captured shortly before his death.

It’s the slow airs, though – mostly drawn from old Gaelic laments, along with a Breton elegy – that imprint themselves most on the memory. While each possesses its own character, all share Mac Mahon’s exquisitely measured timing, his masterly proportioning of space and silence as well as sound, and his astonishingly deft and subtle control of dynamics, ornamentation and harmony.

A similar sense of rapport with the music animates the reels, jigs, marches and step-dances, via his unerring balance between formal rigour and richly nuanced expressive vitality.

Sue Wilson

~

Froots June 2001

Tony MacMahon

Mac Mahon From Clare

Maccd 001 (69mins)

He’s Mac Mahon fom the County Clare now, but he will always be Tony Mac Mahon, the extraordinary and passionate button box player, radio and TV producer, catalyst, enigma, etc. Though he has been recording since the late 1960s (on Topics, Paddy In The Smoke) this collection of his recordings is riveting. He loves the music with a passion and he plays it that way too, whether it’s an air or a reel and he condemns anybody who mucks around with the music. Yet, he will say he sometimes hates the button accordeon, the very instrument he has played all his life. I suspect he is a frustrated piper and the way he plays the button box indicates this with the bass buttons silent until the appropriate phrase can be harmonized like a good uilleann piper can on the regulators.

That passion and intensity may not make life easy for the mere mortals around but Tony Mac Mahon challenges the half hearted, and champions the great unsung musicians such as Joe Cooley and Mrs Galvin, and he is an exceptional musician in his own right. Here we have solo tunes, reels with the likes of Seamus Connolly on fiddle, duets with Joe Cooley and Breton tunes with Barney McKenna. Some of them go back nearly three decades but, this isn’t a retrospective of the days when he recorded Joe Cooley on a winter’s night in Galway in the early 1970s or the grand tour of Ireland, Brittany and France with Barney McKenna, filmed as a series of programmes for Irish TV called, The Green Linnet.

This is great music, uncompromising, almost un-accordeonlike for an accordeonist, and although he has recorded two outstanding albums with Noel Hill, he says this is the first (nearly) solo album since 1972. It is high time he made them regularly because they are a rare treat and a source of great musical enjoyment. Distributed by Copperplate.

Joe Crane

~

The Living Tradition Review

March/April 2001

TONY MacMAHON

MacMahon from Clare

MACCD 001

Tony MacMahon is a box-player from Clare (of course), but he is much more than that. He has been an important force in promoting and maintaining traditional music on Irish radio and television, and in presenting dance music as music to be danced to rather than a spectator sport or – perish the thought – a museum exhibit. He has three fine albums on the Gael-Linn label, two with Noel Hill, and has appeared on numerous other recordings.

This retrospective release contains material recorded throughout Tony MacMahon’s thirty-year career, most of which has certainly not been readily available previously. The sleeve notes are surprisingly reticent about the provenance of some tracks, but it’s clear that a good half dozen of the 17 tracks here are on record for the first time and many more have been rescued from archives. Tony is joined by some of the greats of Irish music: Joe Cooley, Peadar Mercier, Barney McKenna, James Kelly, Seamus Connolly and others. The older tracks are a fascinating glimpse of the tradition a generation ago, and the newer ones show how little has really changed in the heartland of Irish music.

In 70 minutes we are treated to reels, jigs, marches, set dances and slow airs, all played with thought and feeling. Slow airs are something of a speciality with Tony MacMahon, and one of the striking things about this CD is that the slow tracks far outnumber the fast ones. Tony can rattle out a reel as well as the next time-served Clare accordionist, as is amply demonstrated in his fine duet with fiddler James Kelly, but the slow airs are where his singular mastery is most evident. “MacMahon from Clare” includes five fine examples: the opening lament “The Fair-Haired Boy”, the eerie and magical “Port na bPucai”, an unforgettable interpretation of the well-known “Caoineadh Eoghain Rua”, and Maro E Mar Maistress, a fine Breton air which will doubtless become popular, and a wonderful six-minute exploration of “Amhran na Leabhar” which is a challenging and deeply moving piece commemorating the loss at sea of all the manuscripts by the great Irish poet Tomas Rua O Suilleabhain.

Although Tony MacMahon has admitted that his first love is actually Arab music, this collection shows that he has absorbed more than a little of his own tradition and that his time spent with masters such as Joe Cooley and Seamus Ennis was far from wasted. This is not a CD to be taken lightly, but it is to be taken to heart and listened to with care, for here is a man who understands the music of his people.

Alex Monaghan

~

SOUL THEFT

by John Moriarty

‘…and blessings be on you, Tony Mac Mahon – blessings be on you, my very good friend, for the way, and the ways that you bring the music of Ireland to Ireland.

Do mholadh me i gCamus thu!’

John Moriarty

In the mythic imagination of the Indo-Europeans it is the great battle. In India it is the battle between the Devas and the Asuras. In Greece it is the battle between the Gods and the Giants. In Nordic countries it is the battle between the Aesir and the Vanir. In Ireland it is the battle between the Tuatha De Danann and the Fomorians. An old book says this about the Tuatha De Danann :

Batar Tuatha De Danann i n-indsib tuascertachaib an domhuin, aig foglaim fesa ocus fithnasachta ocus druidechtai ocus amaidechtai ocus amainsechta, combtar fortailde for suthib cerd ngenntlichtae.

Living as they then were in the northern islands of the world, the Tuatha De Danann spent their time acquiring visionary insight and foresight and hindsight, acquiring the occult knowledge and the occult arts of the wizard, the druid, the witch – these, together with all the magical arts, until, masters in everything concerning them, they had no equals on the world.

Little wonder then that it was in a great magical cloud that they came to Ireland, landing in the mountains of Conmaicne Re in Connacht. In truth they were a race of Gods but, for all the occult arts at their command, it was their particular delight to be of one mind with the wind and the rain. Great warrior though he was, Ogma knew that a spear that went through him wouldn’t open him out half as much to the otherworld as the call of a curlew calling in a bog would open him out to this world. And Dian Cecht, their leech, he had the look of an upland thorn bush that has long ago yielded to the endless, night and day persuasions of the prevailing wind and is now no more than a current, than the memory of a current, in it.

In the end you could walk through the land and not know they were in it.

Their feathers hanging like seaweed when the tide is out,their tongues the colour and shape of cormorants tongues, the clamour of ocean in their talk, Formorians came ashore.

Forests cut down, rivers rerouted, towers everywhere, it was soon clear that it must come to a fight.

It did. In Magh Tuired.

Never before or since did the battle hag screech as she screeched that night, her mouth bleeding in excited anticipation of the greatest battle that would ever be fought in Ireland. So long loud and piercing was her third screech that it cut gaps in the mountain, it sent the incoming tides back out and as far away as west Munster a man was talking that night to his wife but he didn’t finish what he had to say because , sliced down the middle,the two halves of him and of what he was saying fell either side of her. It was that kind of battle.

As much because of what their wizards did as what their warriors did, victory was with the Tuatha De Danann, or so it seemed.

When the outcome was still in doubt Mathgen, their chief wizard, went chanting forward and so burning a thirst did he cause not just in the mouths but in the minds of the fighting Fomorian warriors that, whatever the cost, victory or defeat not counting now,they must find water, but find it they didn’t because, changing his chant, Mathgen dried up the rivers and streams and lakes and wells of Ireland and there they were, deliriously crossing bogs and climbing mountains, the sound of far-away, illusory waterfalls calling them out over precipices to their death.

What the Tuatha De Danann didn’t yet know was that the chief wizard of the Fomorians could make himself invisible and it was he, altogether more clever than Mathgen, who singlehandedly turned what they had already begun to think of as their greatest victory into their greatest defeat, and this he did by going right to the heart of Tuatha De Danann country, into a fortress there, and stealing their great harp called Harmonizes Us To All Things.

Next day at the very beginning of their victory celebrations, the Tuatha De Danann discovered and suffered their loss.

Putting it to his lips, the chief piper could find no music in his pipe..

Putting it to his lips, the chief trumpeter could find no music in his trumpet.

Putting his bow to it, the chief fiddler could find no music in his fiddle.

Tapping it with his drum stick, the chief drummer could find neither rhythm nor music in his drum.

Opening her mouth, the chief singer could find no music in her voice.

And the curlew didn’t call in the bog.

And the blackbird in the willows didn’t sing.

Asleep that night on the nine hazel-wattles of vision,Mathgen saw what had happened. Macguarch, the chief of Fomorian wizards, had stolen the harp and in stealing that he had stolen the music of Ireland. That very day, their tongues the colour and shape of cormorants’ tongues, the Tuatha De Danann were the new Fomorians.

~

COME WEST ALONG THE ROAD

the video

by Fintan Vallelly

The Irish Times, September 1994, & The Guide to Irish Traditional Music, Gill & MacMillan, 2001

Sitting in Tony Mac Mahon’s editing room in RTÉ must be the closest thing witnessing God at work. A tape of The Pure Drop is running, it has to be shortened to fit a certain time slot. Singer Maighréad Ní Dhomhnaill is forwarded, reversed, forwarded again – her neck moves like an arthritic’s, her smile closes and opens like the Stepford Wives mannequin; Michael Davitt lunges and gesticulates in zig-zag jerks like the Star Wars golden robot. Maighréad is moved forward twenty minutes in time, Gabriel is excised from history, and presenter Paddy Glackin is invented from the future to smooth the transition.

Josef Stalin would be thrilled: on today’s television it is expected and accepted that all images be manipulated. For producer Mac Mahon this is both a profession and a dedicated labour of love. His raw material for all his working life has been the people, the personalities, the sounds and background scenery of Traditional music, his politics have been its aesthetics, style, history, regions, age-group, gender and instrumentation.

Such control has not always been so easy. But in the Come West Along the Road video, a series of RTÉ Traditional Music Archive cuts are availble publicly. In it we can witness the progress of Traditional music in tandem with TV technical innovation. Come West is drawn from RTÉ’s first 21 years (1961-1982), and are researched by Nicholas Carolan and Sadhbh Ní Ionnraic of the Traditional Music Archive in Merrion Square.

Presented by Carolan, these extend almost a fairy-story opportunity to get an out-of-body look at and listen to our very own past. Witness a sweep across thronged, ecstatic Fleadh Cheoil masses: flute, fiddle and pipes players bursting with pride and joy, almost tearful at their new-found confidence in the early-sixties regeneration and recognition of their art. Here too is Willie Clancy with his long, lonely gaze – so real and yet so far away; there a stoic Peadar O’Loughlin (still in his music prime), and a straight-backed Ted Furey miming fiddle to the pipes and guitar of his ridiculously-young sons Finbar and Eddie. A childlike Dolores Keane is visited through the window of her aunts’ thatched house – singing with them in chilling note-for-note precision an allegory for the video series: ‘‘I’m thinking, ever thinking, of those green hills far away.’’ The young Planxty squint through their long locks, Ronnie Drew struts like a Greek God; Sean O’Murchu breathlessly reintroduces himself from the ‘far side’ with the old Tulla ceili band. Migrants like Clareman John Kelly are pursued to Dublin and on their peregrinations around the developing music patterns.

Then Mac Mahon’s Time machine is in Enniscorthy, 1967, where as a youth he himself joins in playing for that most remarkable sean-nós dancer, the late Paddy Ban O Broin. This is heart-wrenching: Paddy charming and radiant in the good suit and shiny shoes, jubilant and appreciative of the potential of the device recording him; a delicate sweep of the toe, a wiggle of the hips, studying his feet in the fancy steps as if treading a marsh path, beaming and inviting as he ends on a mock ballet bow. Jim Donoghue on Clarke whistle, Josie McDermott and Paddy Carty on flutes, singer Mary Ann Carolan, fiddler Sean Ryan, sean nós singer Seosamh O hEanai, piper and singer Seamus Ennis, piper Leo Rowsome, Desi O’Connor on whistle, Luke Kelly, fiddler Denis Murphy and composer Sean O’Riada are all here in this ultimate ‘night-visit’ song, The McCusker’s ceili band from Armagh, Donegal source-singer Neili Ní Dhomhnaill and those who have just got older are here too for the viewer who can take the surprise and pain of the memories their images release. If cassette tapes democratised music, video does that for the visual past. Come West returns the music memories to the people who produced them.

Fintan Vallely

~

An Cairdín Abú

Pearse Hutchinson

Tagairt, RTÉ Guide

January 2001

Má tá pinghin rua fághta agat tar éis na bhféilte – agus is doigh go bhfuil an babhta so ós rud é gurb ionann an tíogar Ceilteach agus Daidí na Nollag – níl rud is fearr go bhféadfá a dhéanamh ná dlúth-cheirnín nua Tony MacMahon a cheannach. ‘‘MacMahon from Clare’’ is ainm dó (MACCD 001), agus tugtar ‘‘Retrospective’’ air freisin.

Mar is eol duit, a léitheoir dhilis – mar atá tugtha le fios agam duit níos mó ná uair amháin i rith na mblianta, tá meas mór agam ar an gceoltóir, Cláirinach seo. Ní déarfainn go séanfadh éinne ar bith gurb é duine desna boscadóirí, ach ní leasc leis an Mathúnach na foinn sin a sheimint, a mhúnlú, a chumadh, ar bhealach, as an nua.

Signs on it tá cú fhonn mhalla le cloisint ar an gceirní seo: An Buachaillín Bán, Port na bPúcaí, Caoineach Eoghain Rua, Amhrán na Leabhar, agus fonn mall ón mBriotáin: Maro e Mar Maistress (?Marbh Atá Mo Ghrá Geal). Níl an Wounded Hussar ann, cé gurbh é sin an piosa fá ndear do Shean Ó Riada a rá leis an Math´nach, nuair a chéad-chuala sé an fonn sin á sheimint aige: ‘‘Níl ceoltóir amháin thú, ach cumadóir ceoil.’’

Bhí an ceann sin beagnach mar phort aitheantais ag an gceoltóir seo, ach le blianta anuas, d’fhéadfaí a rá go bhfuil Port na bPucaí san áit sin. Caithfidh mé a rá, áfach, nach binne liom an tráth seo aon cheann desna foinn mhalla seo uaidh ná Caoineadh Eoghain Rua. Fear fé leith i stair na tíre seo an Niallach rua sin.

Dá bhrá sin d’aontaigh mo chroí le croí an cheoltóra nuair a léigh mé an nóta a scríobh sé faoin bhfonn uasal seo: “Thanking Brendan Mulkere of Clare for playing this soulful air on the fiddle for me of a dull night in London many years ago, banishing depression. I hear it again when I think of our great Ulster chieftain, the victor of Benburb, who died in November 1649 – only months before the arrival of Cromwell.”

Tá roinnt mhaith le tuiscint ó na linte gearra sin, ach níl aon rud is deise iontu ná an dá fhocal seo: ‘‘banishing depression.’’ Gan amhras, ba dheacair iad a léamh gan chuimhneamh ar an gceol-ainm cáiliúil úd: Banish Misfortune. Ach ní chuige sin atáim: cuimhnigh gur fonn mall atá ann, gur chaoineadh atá i gceist – ach chuir sé an ruaig ar an ngruaim an oíche úd i Londain Shasana fadó – agus cuireann fós. Fiú más fonn mall dobrónach é, cuirtear ruaig ar an ngruaim le h-áilleacht, le firinne, le mothúchán doimhin.

Ó pheann an Mhathúnaigh féin a thagann gach nóta sa leabhráinín, agus léimeann siad amach ort leis an splanc is an spleodar cénna, is atá le cloisint sna rileanna ‘s na seiteanna is meidhrí sa ndlúth-cheirnín maorga seo. Agus an tuiscint chénna: ‘‘I can see him as I play this air (An Buachaillín Bán), Séamus Ennis sitting on the side of his bed in Bleeker Street, New York in the July heat of 1964. ‘Stop there,’ he’d say as he guided me in the playing of slow airs. ‘Put the shiver into it now.’ …‘think of the poem as you play.’ He made me learn the words before playing a note…’’ Tá ceacht an mháistir Ennis foghlamtha go smior ag an gCláirineach seo darb ainm Tony MacMahon.

Pearse Hutchinson

~

Review of Mac Mahon from Clare

by Toner Quinn

The Journal of Music in Ireland

Jan/Feb 2001

‘‘I have chosen to play you a lament first, because, in our own time, the loss of love is one of the things that afflicts all suffering mankind.’’

This is how Tony MacMahon introduces ‘An Buachaillín Bán,’ the first track of his new CD, and over the last few months since its release I have been mulling this sentence over. The dual meaning is one reason it sticks with me; possibly he is referring to individual scenarios, as all people at one stage or another suffer the loss of love, but I take great interest in the alternative. Is Tony MacMahon, in the preamble to his performance, which was recorded at the Boston College Gaelic Roots Festival in 1999, actually contemplating the idea of a widespread misery that affects the entire race as it moves through another millenium? This notion halts me, for it is so rare to hear a musician utter such reasons for playing music. Imagine being so moved by the ‘loss of love’ and ‘suffering mankind’ that you would play music!

Perhaps I am sounding ironic. Isn’t it such noble, human emotions that moves all musicians to play? Well, in theory, yes, but rarely do those motives come so passionately to the fore, seldom does a musician manage to excavate so deeply down into emotion that they create such a direct line for the listener – out of the receiver’s world, into the music, and back out again into a renewed world. That, I suppose, is genius, and that is also why it is difficult to listen to this album without being made aware by MacMahon of the burdens the world carries. MacMahon from Clare is the largest call to humanity that has come out of Irish Traditional music for years.

And why wouldn’t it be so, for this music comes from a figure who is, in a sense, both tragic and a cause for celebration. As Mac Mahon has said himself, he had ‘gone away’ from music for some time. This was not always a physical absence, although the first time I met him, aware of the reputation as a player that preceeds him, he was quick to say that he ‘hadn’t played in three months.’ His real absence, I think, and I can only deduce this from snippets of conversation and observation over a few years, was a mental and spiritual one. I overheard MacMahon despair about Irish music, telling a North-African multi-instrumentalist how their music ‘puts us in a big hole in the ground.’ What MacMahon, I think, was despairing at was the globalization tendency towards predictability in music, towards putting music in a box (metaphorically speaking, of course). MacMahon’s way of understanding, thinking, and communicating through music has been at times so far removed from our cultural climate that he has had no alternative but to distance himself from it.

But he could not abandon it, and his work as a producer in television, through The Pure Drop and The Blackbird & the Bell, among many others, appear as MacMahon’s attempt to inject the necessary discernment back into Ireland’s cultural life, if only for it to become intelligible again, and reconnect Irish people with a musical integrity and creativity that was once natural to them.

I once glimpsed a 1970s music programme that MacMahon presented. How different his presentation of the music was to much practise today; using words like ‘discernment,’ ‘fragility,’ and ‘tenderness,’ Ireland and its music were made to appear noble, so strong – far away from the Ireland now embedded with the ‘For Sale ’sign.

~

MAC MAHON FROM CLARE

THE IRISH VOICE

by Don Meade

Tony MacMahon is one of the great Irish traditional musicians of our time. It has been been more than two decades, however, since the famed button accordionist last produced a solo recording. That’s far too long, of course, but MacMahon from Clare was well worth the wait.

MacMahon from Clare includes many true solos, but it also features Tony in collaborations with some distinguished musical friends. Among these are the late bodhrán player Peadar Mercier, tenor banjo pioneer Barney McKenna of the famous Dubliners, and fiddle virtuosi Séamus Connnolly and James Kelly.

Kelly and MacMahon teamed up for the most impressive selection on the CD, an extemporaneous romp through the reels ‘‘The College Groves’’ and ‘‘The Floggin’’’ that has to be one of the most exciting accordion-and-fiddle duets ever committed to disc.

Another particularly affecting track features MacMahon with the late Joe Cooley, his accordion mentor and one of the most revered Irish musicians of this century. This track was recorded during a legendary session in Cooley’s native Peterswell, Co. Galway in late 1972, not long before the master’s death.

Though he has done more than any other player to expand the musical range of the button accordion, MacMahon has also frequently disparaged it, once going so far as to voice regret that there was no bog hole in Ireland deep enough to bury all the accordions in the country. This conflicted relationship with his own instrument is perhaps what impelled MacMahon to bring never-before-heard sophistication to the humble ‘‘box.’’

Having mastered Cooley’s classic style of playing dance tunes, MacMahon began in the 1960s to adapt the majestic slow airs of the Irish-language vocal tradition to the button accordion. Playing with great emotional intensity and making extravagant use of left- and right-hand chords, MacMahon invested the accordion with the grandeur necessary to the ‘‘big’’ traditional songs. He returns to this territory on the new disc with masterly renditions of five slow airs, including ‘‘Amhrán na Leabhar’’ (‘‘Song of the Books’’), ‘‘Caoineadh Eoghain Rua’’ (‘‘Lament for Owen Roe’’) and the Breton ‘‘Maro E Mar Maistress’’ (‘‘My Love She is No More’’).

MacMahon from Clare was independently produced in Ireland.

Don Meade

~

EARL HITCHNER

Best Albums of 2000

Irish Echo, New York

Performers often talk about the ‘pure drop ’in Irish traditional music, its heart and soul, a distillation of the past in the present without resorting to musty, museum-like preservation. Well, ‘Mac Mahon From Clare’ offers a steady stream of the ‘pure drop.’ Tony Mac Mahon is one of the most accomplished button accordionists ever, and this superb recording reflects both the art and the arc of a singular career in Irish music. Exceptional.

Earl Hitchner

~